Children at CCBB. Front sign says “CCBB Occupation – Protected Under Law 6657/2020”. Sign in the background says “When housing is a privilege, occupying is a need!” Credit: @imatheusalves

Wednesday, April 7 saw a true war scene take over Brasília, the not-so-famous capital of Brazil.

On one side, military police teams heavily equipped with rubber bullets, pepper spray, and batons. Tear gas everywhere. Helicopters and drones up in the sky.

On the other, 38 unarmed homeless families standing up to defend the only thing they had: the brittle, improvised barracks they used as shelter and the collectively built, volunteer-run school their children attended.

The reason for the conflict? Governor Ibaneis Rocha had ordered, for the third time during the pandemic, the immediate eviction of all families living in that encampment—popularly referred to as “CCBB”—and the complete destruction of all structures they lived in, including the school.

Most of those people work as recyclable waste collectors. This means they earn their living by searching through the stuff society has disposed of—in the streets, trash bins, and dumping sites—to salvage elements that can be recycled. Albeit stigmatized, their work plays a key environmental role in waste management: it is largely thanks to their service that recycling happens at all in Brazil.

Many had been living in CCBB since the 1970s. Squatting in public land was their only option because of extreme poverty and absence of proper housing. The younger generation was born there. The only roofs over their heads were precarious structures built of wood and metal, with no clean drinking water, bathrooms, or cooking facilities.

The school: a collective effort

Early days of the CCBB school. Credit: @escoladocerrado

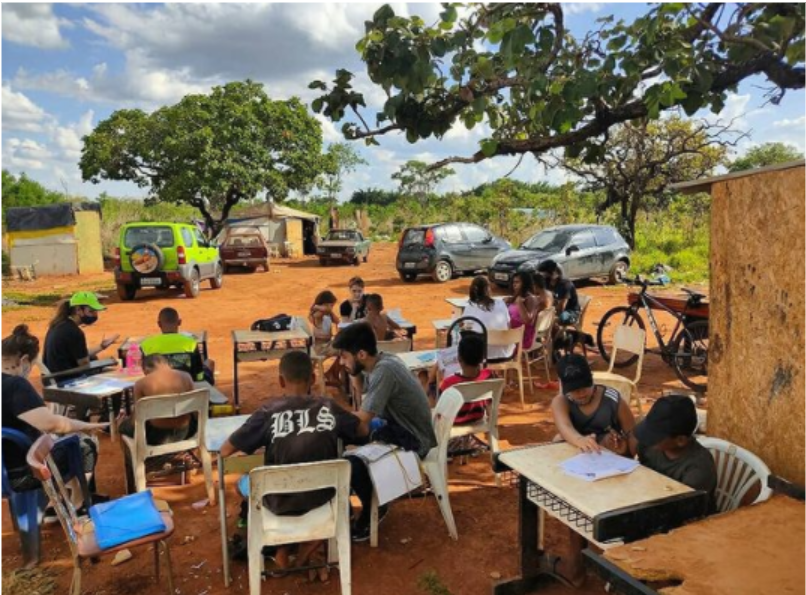

More recently, with the pandemic and the shutdown of public schools, children at CCBB lost all access to education. Remote learning is, of course, a fairy tale where people don’t have electricity or internet connection. That’s why, in July 2020, the idea of building a small school run by volunteer teachers came into being, to preserve those children’s right to learning.

Militants of different political organizations and volunteers teamed up with residents to lead the initiative. Members of a collective called Subverta, affiliated with the Socialism and Freedom Party (PSOL), were key in this process. PSOL was a split from the Workers’ Party after some members disagreed with reactionary decisions/alliances made by the Lula administration. As one of PSOL’s multiple internal currents, Subverta subscribes to the political line of “eco-socialism” and calls for a people-led social and environmental transformation of society.

Another key participant was a mutual-aid group by the name of BSB Invisível (meaning “Invisible Brasília”). Every day, the volunteers running it share the life stories of the city’s poor and homeless people and organize fundraisers to donate essential items. The group’s online campaigns brought financial support to school’s efforts.

School structure collectively built before evictions. Credit: @escoladocerrado

The school started as no more than a few chairs positioned under a tree—and even with tremendous material hardship, it began to thrive. People organized collectively to feed children, create some form of shelter, set up schedules for teaching, and design and grade basic homework assignments.

Teaching subjects like history was often difficult and delicate. As a volunteer put it, “How do you explain to them that they have rights, if they’ve never enjoyed any?”

More and more kids enrolled, their parents trusting the school to provide their children the hope and dignity they needed.

Repression

Residents, militants, and volunteers. Credit: @casadasredesninja

Notwithstanding the beauty of those efforts and the collective strength that was being developed there, the state had different plans for the area.

Without notice, on a regular school day in late March, the police showed up at CCBB to serve an eviction commanded by the governor. “Eviction” isn’t even the right word—they wanted to kick the families out and wipe out the whole complex, in complete disregard of a 2020 law forbidding any such move against squatters during the pandemic.

CCBB residents, volunteers, and militants resisted. Day in day out, for 10 hours a day if necessary, they stood their ground against the state’s efforts. At one moment, the police actually managed to destroy the school and some of the residents’ barracks, but an emergency fundraiser and a massive wave of online solidarity helped them quickly get stuff back in place. Legal wrangling was happening in parallel, as an injunction was granted protecting those barracks from demolitions—but then was soon overturned, leaving families vulnerable again.

Militants and volunteers help defend the school. Credit: @bsbinvisivel

In early April, the Brazilian military police and riot squad finally cracked down on CCBB with the full force of the state apparatus. Militants, volunteers, and supporters were present and, for their own safety, livestreamed the whole thing on Instagram. Thousands of users—myself included— watched in real time as the police tear gassed the area and came in with huge bulldozers to tear it all down.

The self-defense strategy militants and volunteers had been using up to that point was to have people standing under and/or on top of the school’s roof, refusing to leave. For the police, this meant that choosing to move forward with demolitions would deliberately jeopardize people’s lives. The strategy had worked in the past, but this time, the police didn’t care.

Political criminalization

Police surround the school while supporters refuse to leave the roof. Credit: @casadasredesninja

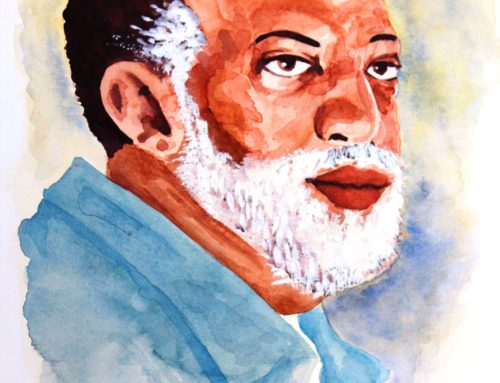

One of the militants standing over the roof when the bulldozers came was Thiago Ávila—a known leader in social and environmental struggles, particularly vocal about the impacts of the agribusiness in Brazil.

Thiago has been targeted by state counterintelligence for years. When the situation at CCBB escalated, he was forced down, carried away, and arrested, as well as three other militants. Most shockingly, their lawyers, who were present at the moment for their protection, were forbidden to come anywhere close.

The moment of Thiago Avila’s arrest. Credit: @imatheusalves

All four arrestees were taken into custody and charged with “environmental crimes,” under the bogus claim that the squatting rested on a protected area. Not only had this “protected” status never been mentioned anywhere before, but also residents and supporters had discussed and incorporated environmental concerns into their daily operation from the get-go. After families were removed, state forces completely cleared and deforested the area, wiping out the native vegetation.

The four militants were released on bail, paid for by a solidarity fundraiser (which raised double the amount needed in less than an hour). They are, however, still potentially facing three years in jail.

Much more than just hate of the poor

Police brutalize CCBB residents. Credit: by Scarlett Rocha, from @bsbinvisivel

Looking at it from a moral lens, many of the hundreds of people watching the massacre live couldn’t wrap their minds around it. Just why? Why would the state be so invested in taking away everything from those who already had nothing? Why deploy so much personnel against… a school? And, perhaps most disturbingly, why was this a priority in the middle of a health crisis? How many vaccines or ventilators could have been purchased with the amount spent on these operations?

Capitalism doesn’t give a damn about morality. If we want to understand why things unfold the way they do and which economic interests underlie apparently nonsensical political actions, we have to follow the money.

As it turns out, that piece of land is in a very strategic, high-profile area. CCBB is about half a mile away from all the most important buildings of the Brazilian capitalist state: Congress, the Supreme Court, the Executive, and the presidential palace (currently Bolsonaro’s residence). It’s a hotspot for development.

Native vegetation burned to the ground after the evictions. Credit: @imatheusalves

Since 2017, there have been efforts underway to turn the area (1.6 million square feet in total) into a so-called “audiovisual hub,” designed to attract national and international capital linked to media and entertainment. The project intends to congregate movie theaters and animation studios, as well as film, TV show, and video game production centers.

As far as national capital goes, the six most important Brazilian TV broadcasters would be offered to move their headquarters into the space. And, internationally, imperialism is doing its job alright: AT&T is a key stakeholder in the construction of the hub.

In 2019, AT&T executives took a trip to Brasília to learn about the future hub and discuss “tax incentives” (code words for profit repatriation). These incentives aim to attract investments from big players in the global entertainment industry. A relevant fact is that AT&T owns WarnerMedia, a multinational media conglomerate with names like HBO, Warner Bros., and DC Comics under its umbrella. During their stay in Brazil, the AT&T executives said they planned to “hire local producers to produce exclusive content for Warner”—which is part of a strategy to compete against Netflix.

Governor Ibaneis Rocha’s decision to remove the CCBB’s residents makes sense considering his own investment interests and those of the fraction he represents.

A capitalist himself, Rocha sides with a fraction of the bourgeoisie whose form of accumulation is real estate development/speculation. He lives in a US$ 4 million mansion with its own private lake. Measly 11 properties and 17 vehicles are registered under his personal name, but his holdings extend far beyond. His realty company owns over 328 properties, including buildings in irregular/unregistered areas (but those aren’t going to be demolished, are they?).

“All the money I make from working as a lawyer,” he said, referencing his other occupation apart from political office, “”I like to invest in real estate. I like to see it [materialize]; I like tangible things. I’m not into the stock market and such.”

When asked about the violent evictions/demolitions happening under his administration, Rocha said he was simply enforcing the law: “We’re not going to let the city become a favela.”

Unique, but universal

“Evictions during the pandemic are illegal.” Credit: @bsbinvisivel

The sheer cruelty of these actions is typical of the lengths capital will go to in dominated nations, but it is by no means a preserve of such countries.

Similar things happen in the US and in Europe all the time, at the core of imperialist powers. Evictions in the US during the pandemic have continued to happen even though they’re supposed to be illegal. In Florida only, 47,484 evictions were filed during 2020 pandemic months, and in March 2021 these numbers began to near pre-pandemic levels.

The whole functioning of capitalist society hinges on violence. We get shocked when we get to see it in real time, but the reality is that our lives are built upon it. The clothes we wear, the food we eat, the gadgets we use are largely produced in horrific circumstances—and, as we see now, so are the movies and shows we watch.

Understanding the economic imperatives behind these atrocities is crucial if we want to stop them. Decisions that are objectively nonsensical from the social and environmental point of view make perfect sense for capital. In the political reign of the bourgeoisie, social ills like homelessness, hunger, lack of education, and environmental degradation are all interconnected: they all bring profit to some fraction of the ruling class and allow the reproduction of the system in their interests.

In the current moment, we’re seeing the bourgeois state ramp up repression to protect those interests at all costs—even if that means violating some of the most basic democratic rights in bourgeois democracy, like the right to be accompanied by a lawyer during an arrest. It’s carte blanche for the police.

Meanwhile, things like the popular school are experiences of collectivity and struggle. They’re places where new social relations are forged, communities where we see tendencies and expressions of a possible future society.

Regardless of whether we agree or disagree with the specific political lines of the organizations involved, the fact is that they were doing something. They understood that solving concrete problems requires getting off the internet and engaging in the real world. They came with an organized approach to build the school, hold meetings with settlement residents, deal with police, and consciously take risks they believed were worthwhile. Rain or shine they demanded the right to housing and education, and they weren’t taking a “no” for an answer.

And this is the kind of stuff we need to be doing.

One type of reaction I noticed among people watching the events as they unfolded was the tendency to look at these groups’ brave, inspiring efforts and treat them as heroes, passively trusting they’ll lead the change we need. The emotional impact of seeing folks risk their lives to be on the front line of police confrontation is undeniable—not only because of the graphicness of real-time violence and resistance, but also because most of us haven’t yet developed the ideological strength and political capacity to do similar things.

When we see people doing stuff we think we can’t, it’s all too easy for us to accept the role of supporters and settle for offering online or financial solidarity.

But this passiveness is actually part of the problem. We can’t delegate responsibility for social change: each and every one of us needs to learn how to lead as well. And there are so many ways do that, so many roles people can play at different levels—it won’t always look like standing over a roof.

Reality is also showing us the urgent need for consciousness-building and organization beyond mutual aid. As I write this, a month has passed since the demolition. Families, now sleeping outdoors, have received food and water donations, which yet again have been taken away by police.

Addressing people’s urgent needs will always matter, but it can’t subsume all political work—or else we’ll never build the unity and strength we need across society to prevent these situations from happening in first place.

Defending experiences like the school would have required a new correlation of forces based on the political organization of the people, locally, nationally, and internationally. Only with a movement will we be able to enforce our demands and keep our victories in place, making sure they don’t get rolled back the morning after.

It’s about time we exercise our conscience and ask ourselves: do we only cry at staged tragedies on Netflix, or are we compelled to take action when they’re happening in real life?

By Laila Martins from Brazil