The title quote is from an article by Pablo Babanegra of Miami Autonomy and Solidarity. It sums up problems within local movements fighting the entrance of Walmart into their communities, and focuses on the construction of the Walmart Super Center in Midtown Miami (which has met intense opposition from many Miami residents). The article is well worth reading.

The coming of a Walmart elicits intense reactions. For many, Walmart is the purest expression of the ills of American capitalism. The company has a record of labor and environmental abuses, a history of eliminating small businesses, lowering wages, and intensifying job insecurity in communities. These things have a cumulative effect throughout the national economy. Walmart is the largest employer in the U.S. and the third largest in the world. Their labor practices are largely replicated throughout the economy. If most jobs at Walmart are low-wage with no benefits, and the corporation engages in fierce anti-union activities, then other employers must follow suit to compete. Proponents of Walmart think of this particular massive corporation as being the ultimate goal of all small businesses — a good, old-fashioned business success.

Midtown Miami has recently become home to countless bars, restaurants, and boutique retailers catering to the young, hip and wealthy. Midtown borders the Miami neighborhood of Wynwood, which has in the last decade been transformed from an industrial, predominantly Puerto Rican neighborhood into a rapidly gentrifying arts district. (Our previous piece for Salty Eggs detailed the development of gentrification in Wynwood.) While diverging from the typical trend in significant ways, it shares many similarities to arts gentrification around the country. Low housing costs and cheap rents attract artists. Through doing their work and organizing events, they give the neighborhood a reputation for being hip. Soon small boutiques open. What was once an unsuitable neighborhood for a big box retailer becomes an attractive option.

In July, a proposal came before Miami’s Planning and Zoning Board, to allow the construction of loading bays on North Miami Avenue as far south as Northeast 29th Street. This would put the proposed site of the Midtown Walmart well within the allowable area. Upwards of 200 people showed up to debate the issue, including representatives of D.D.R. Development Corp, the developer contracted for the construction. The measure was voted down by the Board 9 to 0. Many who were opposed saw this as a brazen attempt by the city to grease the wheels in service to Walmart and D.D.R.

In an article published in the Miami Herald, mortgage broker and real estate consultant Grant Stern argued that Walmart “just doesn’t fit the image that so many have worked to create for Midtown and the Wynwood Arts District.” He also refers to the recent proliferation of galleries, restaurants, and bars as a “thriving experiment in urban renewal.” Although effects on the surrounding low-income neighborhoods are mentioned, the crux of the argument is that the hipness of the area must be preserved. Another problem that opponents cite is the effect of increased traffic. Walmart counters that low-income residents would benefit from a source of low-cost food, retail items, and jobs, and cites the support of Wynwood Historic Homeowners Association. (Though the value of support of the representatives of a homeowner’s association must be questioned in a neighborhood where the vast majority rent).

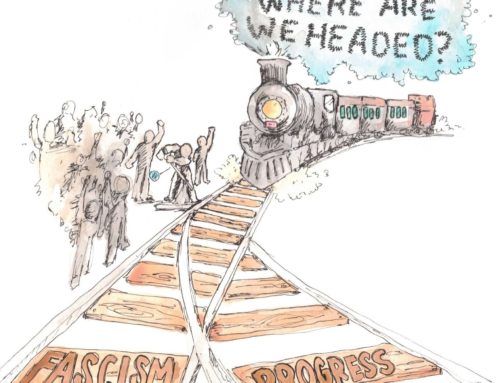

Opposition to Walmart in this community has created a strange alliance of activists, property owners, and factions of the real estate industry. The groups involved have diverging interests determined by their relationship to property and to the multiple layers of gentrification that have occurred. This type of conflict will likely characterize future disputes in Miami. It is not between residents and the corporate giant. Instead, it is an inter-capitalist rivalry for the direction of development. It is a battle between gentrifiers seeking to commodify the “character” of a neighborhood, and corporations seeking to reap profits, with both sides attempting to use the pre-existing community as leverage. The politically and economically dominant elements within these alliances begin to determine the focus and the outcomes, while the poor and marginalized residents become relative non-actors.

This conflict exemplifies the limitations faced regularly by anti-gentrification activists. This is because both views expressed at the beginning of the piece are true: Walmart is simultaneously the ultimate example of the ills of capitalism and the pinnacle of business success. Capitalism as an economic system is dependent on growth and has a tendency to consolidate. This dependence on growth and tendency to consolidate express themselves through multiple economic and political phenomena including monopolization, regulatory capture, and imperialism. These facets of capitalism manifest as corporations like Walmart, entities that are so large that they can alter the market with their actions. This phenomenon can be stemmed temporarily through regulation, but is ultimately unavoidable within the framework of capitalism. The lesson is that we will not be able to take control of our communities without fighting for the economic and political self-determination of our communities. Ultimately, the fight against gentrification is also a fight against the internal logic of capitalism.

Good replies in return of this question with firm arguments and telling the

whole thing regarding that.