By Designer X

Grab a shirt from your closet. Look at the tag inside the collar, and you’ll see where it was produced, listed right next to the size and material composition. Chances are that it was sewn in some other country that you’ve never been to, by someone who lives on the edge of desperation. The current configuration of the garment industry, like most manufacturing industries, is a complicated chain of nightmarish sweatshops and global transportation whose end result is that shirt in your closet. Because of the development and eventual worldwide dominance of neo-liberalism in the last few decades, this is the reality of most of the products that get consumed in the United States.

For capitalists in the garment industry, the globe is viewed as two separate sections. They look at Asia as one option, and Central/South America/the Caribbean as their other option. But usually they like to utilize both, rather than choosing between them. They ping-pong with their business from one country to the next, pitting nation against nation in competition with one another for who can provide goods at the lowest cost. Garment workers in Haiti and Bangladesh are the lowest paid, making two cents per minute ($1.20 per hour). The next country up is Brazil at five cents per minute. In other parts of Asia, the salaries are about the same. In the Dominican Republic the cost of labor to produce a typical, single T-shirt is 29 cents. That same shirt, much like the one you may be wearing now, costs a third of that to produce in Haiti.

This supply chain does nothing to create more than a very small, token number of American jobs (like quality control manager or accountant). Even the customer service representatives that take the orders for clothing (if sold through a catalog or online), are based in overseas call centers. Even with duty rates of up to 40 percent of cost price, the owners are charging consumers a 65 percent profit margin or markup on top of that. In other words, owners are making millions or billions, while the workers who actually sew, press and fold the garments are making pennies.

In addition, the salaries of apparel designers in the states are also losing ground. As of 2012, an apparel designer with five or more years of on-the-job experience (plus a degree) earns about $53,500 annually. In the 1980s, this same job provided $70,000 per year. These salaries are not paid to famous designers, but rather to regular employees of design companies. Even this job, which cannot be easily outsourced (yet), isn’t keeping up with inflation — on the contrary. This demonstrates the failure of capitalism for everyone who works for a living.

This arrangement that garment industry capitalists have developed over the decades has been an outstanding success for them in terms of profits and getting around organized labor in the States, but it is not invincible. If Haitian textile workers all walked off the job demanding at least five cents per minute at the same time that Brazilian workers walked off demanding eight cents per minute, they could start a hemispheric strike that would force the capitalists to give in because they’d have nowhere else to go. There is no machinery in the United States anymore, and these companies can’t turn ships around quickly.

With their global neoliberal agenda supported by favorable trade agreements and institutions such as the World Bank and IMF, capitalists get away with paying overseas workers starvation wages. But workers, if they are organized, could turn the tables on them. Many big companies have all of their eggs in one basket: in one factory, or in one country (or two countries max). They are not as agile as one would expect. It would take them several weeks to change factories — so they could conceivably be held over the ropes for up to 10-11 weeks by organized workers demanding better wages and conditions.

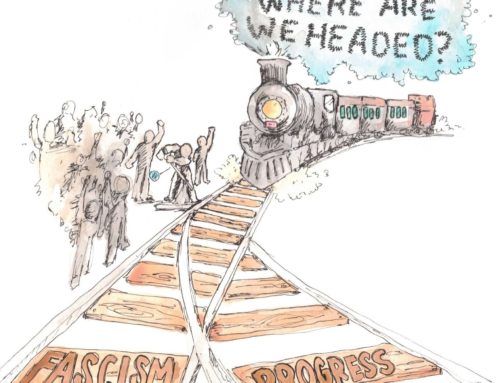

A historic failure of the labor movement in the United States is that is has thus far been unable to form a response to globalization. The only way that the labor movement can recover is by developing an internationalist character. Through a confluence of circumstances, capital has become global. It can move globally with minimal difficulty, and has become capable of producing the world we live in today, with all the associated exploitation, alienation and environmental degradation. Labor, too, must become global through the development of strong, international solidarity networks and coordinated international action. Only then can we reverse the course of neoliberalism, and wake up from the nightmare of domination. The garment industry is possibly the clearest example of this need.