By De Guerre Nom

In July 1944, as World War II drew to a close, delegates from 44 Allied countries met in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire for the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference to draw up plans for the management of the world economy in the aftermath of the most destructive war in history. What became known as the Bretton Woods Conference was the birthplace of the institutional pillars of a newly emerging neoliberal order. Three international regulatory institutions would be conceptualized and formed at this conference: The International Monetary Fund (IMF), the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD, later known as the World Bank) and an international trade organization that would become the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) which through subsequent negotiations would morph into the World Trade Organization (WTO).

While the Bretton Woods Conference was the official beginning of this new economic regime, it actually picked up where the trade conferences of the period between WWI and WWII had left off. Many of the policies that were to be codified at Bretton Woods began to form in this interwar period, mainly through conferences organized by bankers from Allied Nations. Some of the issues that would resurface at Bretton Woods were the subject of conferences such as the establishment of an international bank for post-war reconstruction in Brussels in 1920, and the stabilization of exchange rates in Genoa in 1922. The League of Nations also acted as a precursor to parts of the Bretton Woods system through the negotiation of emergency loans for European countries. This emerging economic cooperation would soon collapse at the onset of WWII.

Near the end of WWII these moves toward economic cooperation were taken up once again but with governments playing a more direct role, especially the newly dominant United States. During the interwar period the U.S. largely stayed out of the internationalist projects of Europe but this behavior changed during the war as many in policy circles began to believe that an isolationist stance would lead to the spread of communism. The Bretton Woods Conference reflected this new attitude and was preceded by two and half years of negotiations between the U.S. and Great Britain. Most of what was discussed at the conference had already been decided through bilateral agreements between the U.S. and the British, making Bretton Woods largely a formality. These proposals sought to create a world of expanding trade and easily convertible currencies which reflected the role of industrially dominant countries in drafting the agreements. During these negotiations the Joint Statement on an International Monetary Fund was drafted as a framework for the conference in Bretton Woods.

The purpose of the IMF was to provide economic security by regulating exchange rates between national currencies and to provide loans to governments with balance of payments problems. All of the participating countries agreed to value their currencies relative to the dollar and the value of the dollar would be pegged to the price of gold. Additionally, the conference established the IBRD which would help to finance the post-war reconstruction of Europe. The IBRD was joined in 1960 by the International Development Association, an organization designed to provide loans to poor nations for development, forming what is now known as the World Bank. At Bretton Woods it was also widely agreed that an additional International Trade Organization (ITO) would be necessary to stabilize trade.

The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) would be formed in 1947 at the UN Conference on Trade and Employment to reduce tariffs and other barriers to trade and to facilitate the movement of capital. Stipulations for punishing member countries that violated trade agreements were also included. GATT would later be replaced by the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995.

In its initial decades, the Bretton Woods system was focused on post-war reconstruction and lending went primarily to the national governments of Europe until the early 70’s. Due to the devaluation of the British Pound in the late 60’s and subsequent devaluation of the dollar, the U.S. opted to no longer peg the value of the dollar to the price of gold; other governments soon followed. This coincided with the rise of neoliberalism, a form of revived economic liberalism which rejected any state intervention into the economy and relied on markets to regulate themselves. Eliminating state influence in the economy and reducing trade barriers, neoliberals believed, would deliver economic growth and increased prosperity for all.

Finally, the newly formed Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) began to increase the price of oil in 1973 which led to increased energy costs in both rich and poor oil importing nations. Wealthier nations were able to absorb the costs while many poorer nations began to experience balance of payments issues. The IMF and World Bank began shifting their lending from European countries to the “third world” as poor nations with desperate governments began requesting loans. Soon lending became differentiated based on the perceived credit worthiness of the country making the request. Conditionality, basing loans on the borrower’s acceptance of measures intended to promote expanded trade and growth, became the norm. The IMF thus emerged from the 70’s a vastly different organization and one that had also become much more powerful, entangling most of the world in the Bretton Woods system.

Today the IMF, World Bank and WTO are integral components of imperialism. Because of capital’s unceasing need to expand, the IMF and World Bank have become the primary tools of capitalist penetration into previously non-existent markets. This is done through a variety means, one of the most prominent being the use of Structural Adjustments as conditions to loans.

Structural Adjustments are measures that are implemented in borrowing nations to eliminate balance of payments problems and promote growth and economic self-sufficiency. What this amounts to is the elimination of subsidies and tariffs, the privatization of state industries and the cutting of health and welfare programs. This leads to an influx of foreign products into markets once dominated by local producers and disastrous consequences for the local population. The WTO figures into this system by limiting the methods nations can use to govern their economies with the threat of sanction. While the stated purpose of these policies is to promote growth and self-sufficiency, they often have the opposite effect and lead to further poverty and reliance on loans.

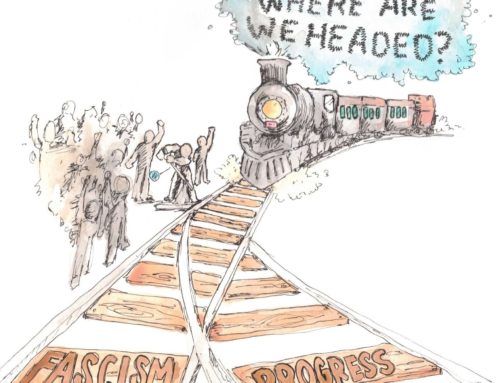

The Bretton Woods system has undergone many changes since its founding and today we are living through an equally important development. Neoliberalism has been entrenched as the dominant ideology of the global economic regime and in recent years its most destructive policies have been turned back on the developed world. The governments of Europe and North America have reacted to the current economic crisis in typical neoliberal fashion: cutting budgets and enacting harsh austerity on their citizens. The introduction of these policies to Europe and North America has resulted in an explosive situation and that has led millions to seek out alternatives to capitalism and imperialism.

Though it’s not clear what the result of these developments will be, it’s clear that the struggle against and the eventual dismantling of the Bretton Woods system will be critical to emancipating ourselves from imperialism and capitalism.

[…] not occur through some natural flow of “free markets” but through intentional policies, laws, regulations and institutions founded specifically for regulating in the interests of capitalists and their corporations. Often […]