by Kiki Makandal, One Struggle (NY) and the Batay Ouvriye Solidarity Network

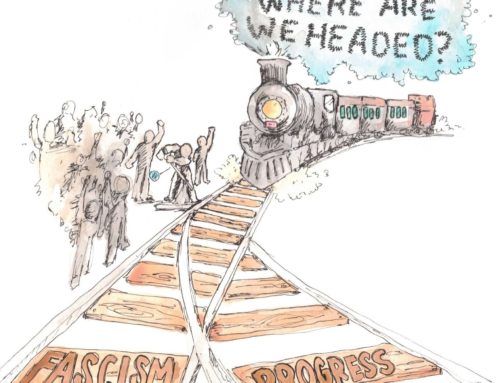

To understand the impact of nine years of UN military occupation on the lives of workers in Haiti, one really has to go back to the original push for neoliberal reform in Haiti since the early 1970s, because this most recent intervention and occupation is only the most recent implementation of this policy.

By neoliberal reform, we mean the push for “free trade” (reduction of import tariffs, quotas, etc.), privatization of state-run enterprises, reduction of state social programs (such as health and education), currency devaluation and stabilization, promotion of sweatshop assembly manufacturing and agro-industry sectors that support the interests of large multi-nationals—that is to say all the policies that have systematically impoverished workers throughout the “third world” and enriched billionaires and multi-national corporations.

The ’70s saw the original start of the assembly manufacturing sector in Haiti, which was facilitated by extremely low wages, the absence of unions due to the repression of the Duvalier dictatorship, and the huge tax incentives granted to foreign investors. This quickly led to Haiti becoming the top producer of baseballs in the world, a significant producer of electronic goods and various assembled textile products.

However, the development of sweatshop assembly manufacturing in Haiti was constrained by conditions inherent to the reactionary dictatorship: a crumbling economy due to a failing agricultural sector and archaic economic structures, very poor infrastructure (no electricity, very poor roads and port facilities, etc.), rampant corruption, and an underlying potential for political upheaval due to decades of intense repression. Indeed, despite the rise in assembly manufacturing, crumbling economic structures fostered political upheaval in Haiti, which led to the 1986 ouster of Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier into a golden exile facilitated by US Air Force cargo planes.

The imperial neoliberal “plan” was then to institute some kind of “democratic” figurehead reform that would implement the full range of neoliberal reforms that the preceding dictatorship had been unwilling to take part in, particularly the privatization of state run enterprises. To this end, a new constitution was drafted and Marc Bazin, the “Chicago Boy” World Bank economist was lined up as the candidate of choice in UN monitored presidential elections. However, this plan was foiled by the last minute candidacy of a Jean-Bertrand Aristide, a popular populist priest, an advocate of liberation theology who had once put out a record entitled “Capitalism is a mortal sin.” Aristide ran away with the election in December 1990, but was overthrown by a US sponsored military coup after less than eight months in office and after attempting to increase the minimum wage. This led to a 3-year impasse since the imperial “neoliberal order” had just embraced the electoral process as its main avenue of reform and renounced military overthrows, at least publicly. These 3 years of military rule in Haiti were used to purge the populist movement by killing more than five thousand of its supporters, wrecking and bankrupting the Haitian state, and setting the stage for a more compliant new regime. Aristide was induced to sign on to neoliberal reform and brought back into office by 24,000 US marines in September 1994. This created the first precedent for UN “humanitarian” military intervention requested by a “constitutional” head of state, in effect forfeiting that state’s sovereignty, and established the MINUAH, first US-UN military occupation of Haiti, which lasted until 2000.

The imperial “plan” was to move ahead with the full agenda of neoliberal reforms, but this did not go so smoothly. The political situation was fraught with contradictions, since the populists had to be constrained by the same reactionary right wing forces that the occupation was supposed to disarm. Needless to say, there was very little disarmament, and an intricate process of power alliances ensued where the populist movement assimilated some of its former foes by policies of “reconciliation” offering them juicy positions in the government. Aristide dissolved the Haitian Army while the imperialists strived to control the newly formed police forces. The populist imperative was to “rebuild” the state under the authority of Aristide, while the imperial “plan” was to divide and conquer, to foster more compliant right-wing political forces that could prevail in new elections.

Throughout this period, populist forces preserved their rule by compromising their social agenda and creating a new “bureaucratic” faction of the bourgeoisie, which quickly earned the moniker of “Gran Manjè” or “Big Eater,” amassing their fortunes through corruption. In 2004, growing popular dissatisfaction and right-wing opposition to Aristide’s second term enabled a small CIA-sponsored military contingent of about two hundred armed mercenaries of ex-army and ex-paramilitary members to march into Haiti from the neighboring Dominican Republic, lay siege to the capital and demand Aristide’s ouster. Once again, US cargo planes carried Aristide into exile. This led to the current iteration of US-UN intervention in Haiti, the MINUSTAH, initiated on June 1, 2004 with the landing of a contingent of troops from Chile. This time, the US was overwhelmed by the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan and chose to delegate the stewardship of this intervention to aspiring emerging regional powers in Latin America and Brazil, which claimed the military leadership of the UN mission, although the political leadership has always remained with the US embassy.

Right away, a provisional government was set up through “constitutional” manipulations: the Latortue government. His administration was recognized by the United Nations, the United States, Canada and the European Union, while being denied recognition by a few governments, including those of Jamaica and St. Kitts and Nevis, Venezuela and Cuba, as well as the African Union. The same neoliberal agenda was promoted, this time through the ICF (Interim Cooperation Framework), promising hundreds of millions of dollars of foreign investment for the implementation of these policies, and new elections were scheduled in 2006 with an abundance of pro-neoliberal candidates. But once again, René Préval, a last minute populist candidate, former prime minister under Aristide, former president after Aristide, known as “Aristide’s twin brother,” won the election and resumed the policies of compromise, corruption, power grabbing and “stalling” that were the hallmark of the previous populist administrations.

This was the situation until the January 12, 2010 devastating earthquake that destroyed much of Haiti’s crumbling infrastructure, particularly in Port-au-Prince (the capital), and made more than 300,000 victims plus a million and a half internal homeless. Immediately, this moment was seized as a new opportunity to implement “the plan.” The ICRH, (Interim Commission for the Reconstruction of Haiti) was formed, promising 11 billion dollars in assistance that was tied to various programs that facilitated neoliberal reform. And new elections were called for. At the insistence of Haiti’s “friends” in the “International Community,” the Haitian general election, originally scheduled for February 2010, was postponed to

November 28—in the rubbles of the earthquake, in the midst of a cholera epidemic which had spread through the negligence of UN occupation forces from Nepal, and after hurricane Thomas had inflicted further devastation. This same “International Community” then intervened through the OAS in a recount of election results to push through their favored candidate Michel Martelly, an outright pro-business right- wing candidate. Martelly then won the second round of the elections and at once declared: “Haiti is open for business.”

Since taking office in 2011, Martelly has engaged in the same outright power grabbing of his predecessors, while postponing new elections indefinitely, with the tacit approval of this same “International Community.” So, this brief historical recap shows us that this current UN-US proxy occupation of Haiti, using troops from 29 different countries from 4 different continents, is only a new chapter in the continuing attempt to implement neoliberal reforms in Haiti, the poorest country in the western hemisphere. It has taken several coup d’états, the murder of thousands by right-wing death squads, several flights of US cargo planes taking away former Haitian presidents, several occupations, a new constitution, an earthquake, a few hurricanes, and many attempts at elections to get to this current state of affairs where the “International

Community” is finally “having its way.” But Haiti is still embroiled in turmoil: the popular masses are still threatening social upheaval, the ruling classes are still divided in their power grabbing projects, and the imperialist agenda is still puttering along, not quite able to fully implement its “plan.” It has succeeded in destroying the Haitian national economy; Clinton has even apologized for free trade policies that led to the destruction of rice agriculture in Haiti. But there is still over 70% unemployment (the “Free Trade Zones” and industrial parks that were supposed to employ a massive cheap labor force only employ a few thousand workers), and the economy is a wreck—with the drug trade, contraband, foreign aid, and remittances from expatriates forming the bulk of the GDP.

To summarize, the impact of this continuous series of imperialist interventions and occupations on the working class in Haiti has been disastrous. Constant repression has been deployed against working class movements and their organizations. Successive coups have been followed by intense repression of worker organizations, which have had to rebuild themselves over and over. Generalized impunity for bosses has been prevalent even under populist administrations, where systemic violations of worker rights have been undeterred and even aided at times by state-sponsored repression. MINUSTAH forces even directly

intervened in 2009 to squash protests by workers who were demanding an adequate adjustment of the minimum wage. MINUSTAH tanks, helicopters and troops were deployed to block worker protests and mobilizations. In this case, MINUSTAH troops were the chief enforcers of the “cheap wage” comparative advantage being promoted by imperialism and the Haitian ruling classes to attract foreign investment.

Under occupation, Haiti has become the “Republic of NGOs,” and these thousands of NGOs have not only contributed to systematically weaken the Haitian state, but are also actively co-opting working class movements.

Throughout these last 28 years of interventions, the nominal daily minimum wage in Haiti has risen from 15 gourdes in 1980 (US $3.00) to 200 gourdes in 2013 (US $4.55), but its real value today is only about half of the 1980 minimum wage (under the Duvalier dictatorship), while rampant inflation continues to eat away at workers’ incomes.

But the US military interventions and occupations in 1915-34, and by proxy in 1994-2000 and 2004 up to the present, have still failed to break the will of the Haitian popular masses to rebel, and the determination of Haitian workers to fight for their rights.