By Camilo Mejia

My two main direct experiences with US imperialism were first when I lived in Sandinista Nicaragua, where both of my parents had been active insurgents against the Somoza dictatorship and later part of the revolutionary government; and second as an invader and occupier while serving in Iraq with the US military in 2003. While the reasons behind my joining the US army deserve future exploration, the aim of this article is to talk about US intervention in Nicaragua, which neither begin nor ended with the four-decade US-backed Somoza dictatorship.

In reality, or at least in my vague recollection of Middle School Nicaraguan history, the first gringo conquistador who set his sights on my country was Tennessee-born filibuster William Walker. Walker did not travel to Nicaragua as an official government representative, but he was a strong advocate of slavery and of the manifest destiny doctrine which, along with his corporate financing and aims, earned him Federal support and sympathies. Walker’s original mission had been to stabilize the country to ensure that civil war between the two main political forces, the Liberal and Conservative parties, did not interfere with US commercial interests. Namely, he traveled to secure a commercial route between New York and San Francisco by ship through Rio San Juan, on the east across Lake Cocibolca, and north by train on the west coast. While Walker’s manifest destiny-driven commercial adventures were applauded in the U.S., his grandiose conqueror ambitions eventually spun out of control. His rich private sponsors withdrew support and a coalition of Central American armies chased him out of the region in 1957. In 1860, back in Central America, he was captured by the British Navy and delivered to Honduran officials, who executed him by firing squad.

Between Walker’s personal intervention in Nicaragua and the beginning of the 20th century, U.S. interest in the region was minor. Around the time of the Spanish-American war, as the US began to seriously campaign to build the Panama Canal, U.S. interest in Latin America grew strong. Control over the Panama Canal would not only give the U.S. an upper hand over Europe militarily in the region, but also facilitated trade by cutting sea routes in half.

The exploitation of Latin American land and natural resources by American companies, like United Fruit Company (officially established through a merger in 1899), was a primary reason why between the Spanish-American war (1898) and the Treaty of Paris (1934), the U.S. engaged in a series of military interventions in Central and South America and the Caribbean to ensure commercial and military dominance.

The Nicaraguan political arena during that time was similar to when Walker was there. The two elite parties, Liberal and Conservative, continued quarreling for political and economic control. This often meant both selling national resources to United States corporations, but also resulted in a volatile and unstable situation that made those corporations nervous about their investments and created favorable conditions for intervention.

In October of 1909, Liberal president José Santos Zelaya engaged Germany and Japan in conversation about the construction of a Nicaraguan canal (which would threaten the Panama Canal and therefore American interests). A civil war broke out between Zelaya’s forces and those within Nicaraguan government who favored US interests, mainly from the Conservative party. The U.S. government declared Zelaya a dictator and sent 400 Marines to support the rebellion. The Marines landed on the Atlantic Coast under the pretense of protecting the lives of foreigners in the area. Aside from a brief break in 1925, that protection remained in Nicaragua until 1933, and is more accurately described as military support of the pro-US interests Conservative party.

Capitalizing on continued rivalry and unrest within Nicaraguan politics, the U.S. easily exerted control throughout the region through its military presence and financial influence, preventing construction of a Nicaraguan Canal and opening doors of Central American resources to US companies.

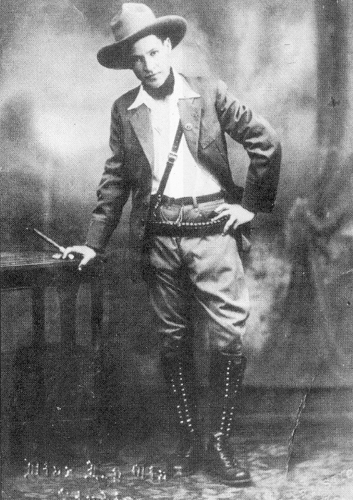

But Nicaraguan history would take a radical and significant turn in 1927 when Augusto C. Sandino, son of a wealthy landowner and his female servant, joined the struggle for national sovereignty. Sandino’s experiences in exile in Mexico cultivated anti-imperialist, nationalist ideas. Later when working at a gold mine in mountainous northern Nicaragua, he recognized similar struggles and decided to join arms with Liberal Generals who were fighting what they considered to be a “vende patria” (“country-selling” traitor) pro-U.S. government. Sandino’s eloquent national liberation ideas and brilliant hit and run guerilla tactics quickly turned him into both a Nicaraguan hero and international icon of anti-imperialist struggle. It is said that Sandino’s elusive military tactics later formed the basis of official U.S. military guerilla warfare tactics.

Under financial strain from the Great Depression and after massive efforts, including some of the earliest aerial bombings in history, failed to capture Sandino, the U.S. brokered a deal, known as the “Espino Negro Treaty,” between the warring political parties. The terms included withdrawal of U.S. troops from Nicaragua after the 1932 presidential elections, disarmament of all sides, and training and establishment of a professional Nicaraguan military known as the National Guard. The National Guard was to be trained and supervised by remaining U.S. military advisors, and was allegedly created to provide a path to Nicaragua’s democracy.

While Sandino viewed the US-trained and controlled National Guard with mistrust, he recognized the election of candidate Juan Bautista Sacasa, a former deposed Liberal vice-president. In 1933, an ambush by National Guard Forces, under the command of General Anastasio “Tacho” Somoza García, succeeded in assassinating Sandino on his return from talks with the president. His brother Socrates and two of his generals, Estrada and Umanzor, were also killed. The whereabouts of Sandino’s body remains one of Nicaragua’s biggest mysteries.

With United States support and complete control of the National Guard, the Somoza family ruled Nicaragua for 43 years, either by winning presidential elections through intimidation and fraud, or by promoting candidates who would govern in the family’s interest and serve as U.S.-puppet presidents. The first of the three Somoza dictators was assassinated in 1956 by a poet and music composer named Rigoberto López Pérez, who shot him six times at point blank while at a party.

That patriarch dictator was succeeded by his son Luis Somoza Debayle, who was president until 1963, but ruled Nicaragua until he died of a massive heart attack in 1967. During that time, around the year 1961, a group of young Nicaraguan revolutionaries decided to adopt August C. Sandino’s name to organize resistance against the regime. They founded the Sandinista National Liberation Front, or FSLN (Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional), and by the early seventies became an effective rebel military force against the regime’s feared National Guard.

Although the Somoza dictatorship was corrupt, brutal and quite disliked internationally, it enjoyed the full support of the United States because it was considered an anti-communist stronghold that always served American interests. During World War II the United States confiscated significant amounts of Nicaraguan land and property owned by German citizens and sold it to the Somoza family at ridiculously low prices. The Somozas in turn used their power and position to sell Nicaragua’s natural resources with huge concessions to American corporations, and allowed CIA-trained Cuban dissenters to use Nicaraguan ports during the failed Bay of Pigs invasion. It is said that FDR once referred to Somoza by saying “Somoza may be a son of a bitch, but he’s our son of a bitch.”

After Luis Somoza died, his brother Anastasio, a West Point graduate and the second most powerful man in Nicaragua, assumed power. While his brother’s rule had been gentler than their father’s, Anastasio’s response to the Sandinistas and those who supported them was quite brutal. After the 1972 earthquake leveled Managua and killed 10,000, Somoza’s corruption extended to exploitation and blatant theft of international aid. His rule eventually became so inhumane and corrupt that the U.S. government was forced to respond to undeniable evidence of human rights’ violations by finally withdrawing support from the regime.

The people were fed up with corruption and brutality and increased support for the Sandinistas, who had become more sophisticated in their guerilla tactics. On July 18, 1979, the FSLN forced the last of the Somoza dynasty out of the country, and the next day celebrated the triumph of the Sandinista Popular Revolution. Anastasio Somoza Debayle was denied asylum in the United States. He then fled to Paraguay, which was under the dictatorship of Alfredo Stroessner, and where he was ambushed and assassinated by a group of Argentinian revolutionaries.

When the FSLN took power, changes were made. All land owned by the Somoza family and its allies was nationalized. There was a land reform, a literacy campaign, fixed prices for basic food staples, freedom for urban and rural workers to unionize. The death penalty and practices of torture were abolished; social services for the population and access to healthcare and education were improved; equal rights for women were sought, and more.

These changes, coupled with the Sandinistas’ close ties to Cuba and the USSR, made the United States quite anxious about the young revolution. Washington responded by financing a group of counter-revolutionary forces collectively known as “The Contras.” The biggest of these groups was formed by ex-National Guard officers, and their tactics as rebels did not differ much from their tactics while in power. From their headquarters in the U.S.-Honduran base of Soto Cano, the Contras launched terror campaigns against defenseless peasant communities, utilizing rape, torture, dismemberment, and other horrific practices, learned from CIA advisors, to undermine popular support for the Sandinistas. Meanwhile the CIA was carrying out a series of bombings of Nicaraguan harbors, sinking Nicaraguan and other foreign ships, and conducting other acts of terrorism against the country.

While the U.S. officially stopped aiding the Contras under political and international pressure for human rights violations in Nicaragua, high officials within the Reagan administration continued to finance them with money obtained from secret weapon sales to Iran, which was at war with U.S. ally Iraq. This illegal funding of the Contras became a huge scandal, known as the Iran-Contras affair. Eventually the International Court at The Hague found the US guilty of committing acts of terrorism against Nicaragua and ordered it to pay $16 billion in damages, which the US ignored.

The continued support of the Contras by the US forced the Sandinista government to sustain a military draft. Military expenses, coupled with an economic embargo imposed by the U.S., made the situation of many Nicaraguans quite precarious. Opposition political parties, private media outlets and the hierarchical Catholic Church worked in cahoots to undermine popular support for the revolution. By the 1990 elections, in spite of all positive change and promise of the revolution, and exhausted by poverty and a decade of war, Nicaraguans voted off the FSLN, and elected instead a pro-U.S. coalition of political parties, made up of the old Liberal and Conservative guard. Although the Sandinistas stayed in control of the military, all other power was ceded to the new government, whose agenda included waving the $16 billion debt the US had with Nicaragua and returning confiscated land, as well as opening the country once more to rapacious foreign investment.

A succession of three oligarchic pro-U.S. governments lasted a total of 16 years. Prior to the 2006 presidential election, PLC’s (Liberal Constitutionalist Party) strongman and ex-Nicaraguan president Arnoldo Aleman faced 20 years in jail for corruption. Aleman’s party is a direct descendant of the Somozas’ political party, and many of its supporters are not shy about recognizing that. Keeping up with the Somocista tradition of embezzlement and theft Aleman amassed a fortune while he was president estimated at approximately $100 million, which given the severe poverty of Nicaragua was considered among the largest in Latin American history.

The Sandinistas signed a pact that would progressively reduce Aleman’s sentence, were able to amend the constitution in order win the presidency with 35 percent of the vote and only a 5 percent advantage over the first runner up. With the opposition party split, the FSLN also kept a majority of seats in parliament, which allowed it to make further changes in order to consolidate power. The PLC and FSLN also became the bosses of the Supreme Court and the Supreme Electoral Council, the fourth power.

Although the 16 years of Liberal Nicaraguan governments had been marked by corruption, American corporations had enjoyed unrestrained access to the country’s resources and labor at extremely low prices, so relations had ran smoothly between the two nations. But with their old anti-imperialist nemesis back in power, the United States government was now frowning upon corruption.

Although the Sandinistas reversed many of the neoliberal measures imposed by the U.S. during the prior 16 years of Liberal governments, they were no longer playing the armed revolutionary movement card. Upon returning to power, the FSLN’s long time leader, and now president once again, let the world know that private investment would be welcome to stay and would continue to thrive. Instead of going back to revolutionary rhetoric, the Sandinistas decided to re-shape themselves into a government of national reconciliation, and sat at the table with the World Bank, the IMF and the Central American Free Trade Agreement to negotiate and discuss favorable conditions.

https://www.telesurenglish.net/news/Nicaragua-The-39th-Anniversary-Of-A-Triumphant-Revolution-20180719-0012.html

While neo-liberalist foreign investment is alive and well in Nicaragua, the Sandinista government has been able to launch programs of social uplift that have created jobs and nourishment for hundreds of thousands of Nicaragua’s poorest citizens. Its rural hunger-eradication programs have enabled the country’s peasantry to reclaim itself as a force of self-sustainability, created a banking system run by peasant women, and provided work to small- and medium-size businesses. The Sandinista government has also been able to alleviate the housing crisis, provide healthcare and higher education, and enact labor laws that benefit common people. The rebuilding of roads and subsidies for the transportation sector have enabled many more people to become connected and conduct trade. The government has also passed laws protecting pensions, labor rights, and rights for domestic workers.

Though the United States has refrained from overt direct intervention, it has continued to attempt to shape the Nicaraguan political landscape by financing opposition parties, NGOs, and so-called Civil Society groups that aim to discredit the government and create the illusion of a dictatorship in need of a generous, humanitarian U.S. invasion. However, far from their guerilla-warfare, revolutionary days, the FSLN has learned to play the game of Western-style representative democracy. So, corruption and fraud are cards played by everyone at the table of electoral democracy, as long as the house continues to make money. True, throwing a few chips at the Nicaraguan people while letting transnational companies have access to cheap resources and labor is far from revolutionary, but is keeping the neoliberal brand of capitalism from brutally oppressing the Nicaraguan people, and that is enough for the time being. Shaking off intervention for good may seem to some too ambitious a goal, but if it is to ever happen it will require a massive movement of international solidarity in defiance of imperialism, wherever imperialism happens to be.

You’re a fucking piece of worthless shit. You can go fuck yourself up a tree. I swear to god you’re a fucking moron. Capitalism is the lifeblood of prosperity- of innovation. You think that because you’re stuck in your mom’s basement that you are entitled to try and destroy and economic system that has helped millions of people climb out of poverty. News for you buddy, you don’t. So go fuck yourself and keep your opinion to your fucking self.